HSP summer 2017 teams from Dusty shoes, Aldersgate UMC Church and the Stanton district completed a water tank for the 35 families of Nuevo Chuicutama. The community was facing months without water due to changes in weather patterns and increasing population.

A CULTURAL LANDSLIDE

A rural indigenous community's forced relocation by a landslide has induced profound cultural changes that challenge the underlying social contract in place for thousands of years. The conflicts and consequences unearthed by the geographical change illuminate many of the challenges facing humanity today.

IRRIGATING THE FUTURE

The Nedee Bikiyaa's organic garden located on the White Mountain Apache reservation in Eastern Arizona is an example of Native teachings concerning complexity achieved through simplicity.

The Nedee Bikiyaa's organic garden located on the White Mountain Apache reservation in Eastern Arizona is an example of Native teachings concerning complexity achieved through simplicity.

As a symbol, the garden represents a return to food sovereignty and traditional beliefs about how to live in harmony with creation. As a health intervention, the garden is an example of the logical next phase of nutrition education for a population suffering high rates of diabetes and other ailments resulting from the loss of traditional food systems. As a program, the garden provides valuable behavioral health impacts by increasing cultural awareness and pride in valuing traditional knowledge. As an organization, the garden represents the creation of social capital to restore tribal connections and cooperation. As an enterprise, the garden provides market-oriented activities to promote social entrepreneurship.

Ndee Bikiyaa translates as the People's Farm from Western Apache language. The farm includes grain production and a growing organic garden. While the economic and social objectives of Ndee Bikiyaa are important, possibly the most significant impact of the garden is to increase the amount of water being utilized by the tribe to protect their future sustainability regarding state and federal water allocation rights.

Many people imagine Arizona as a desert covered in cacti and barren yet colorful rock formations. What they do not know is that the Mogollon Rim marking the Colorado Plateau runs through the region and rises as the White Mountains. The White Mountain Apache Tribe's homeland is the source of water for much of populated areas of the SouthWest.

The US government has legally treated Indigenous nations as domestic dependent nations in a relationship that Chief Justice Marshall in the case Cherokee Nation v. Georiga (1931) described as being like that of a "ward to its guardian." The practical result of this status is that the federal government retains the power to allocate resources and in extream cases terminate reservations.

Tribal nations of Arizona are concerned with the growing scarcity of water and the unrestrained growth of non-native demands on their limited water. This could create a crisis situation where historical precedent and treaty obligations are again forgotten.

Congress passed the Colorado River Basion Act in 1968 and authorized The Central Arizona Project ("CAP) to construct systems of pumps, canals, and laterals bringing over 1.4 million acre-feet of Colorado River water supplies to central and southern Arizona, including Phonix and Tuscon. The municipal, industrial and agricultural demands by non-natives have exceeded the water made available by the CAP and represent a significant threat to native nations. (1)

By choice or chance, the federal government also destroyed much of the White Mountain Apache centuries-old irrigation systems and relocated tribal members away from agricultural lands to model communities designed for assimilation into urban areas away from the reservation.

A critical legal precedent for defending the future viability of the reservation is the "federal reserved rights doctrine." The principle was established by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1908 in Winters v. the United States. "In this case, the U.S. Supreme Court found that an Indian reservation (in the case, the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation) may reserve water for future use in an amount necessary to fulfill the purpose of the reservation, with a priority dating from the treaty that established the reservation. This doctrine establishes that when the federal government created Indian reservations, water rights were reserved in sufficient quantity to meet the purposes for which the government granted the reservation." (2)

The federal reserved rights doctrine provides reservations with a senior claim over other parties in water disputes as long as they can verify that the water use is in agreement with the recognized purpose of the reservation. For the White Mountain Apache, agriculture is critical because the expressed purpose for the formation of the reservation was to maintain a livelihood as farmers. Thus, the amount of water reserved was that sufficient to irrigate all of the "practicably irrigable acreages" (PIA).

The Colorado River Compact of 1922 has brought state governments into the water managing process with the federal government. The federal government represents the First Nations in the informal process with the states for resolving water issues. This means that the tribes have to depend on an executive branch of the federal government to advocate for Indigenous rights. That has not always worked out well for tribal people.

Today, tribal members feel it is critical to irrigate as much reservation land as possible and to stimulate a return to gardening and farming to demonstrate their livelihood as farmers. It is plausible that the participating states in the Colorado River Compact could establish ratios based on current use through the McCarren Amendment, which returns substantial power to the states with respect to the management of water and thus could deny the Apache use of the water that originates 0n their ancestorial homeland.

The Highland Support Project networked the Ndee Bikiyee farm with Tempe, Aldersgate, and New Creation United Methodist Church to install an irrigation system for the organic garden managed by Clayton Harvey. Jo Costin and Michel Keller provided valuable consulting services in the construction of a solar well house and the completion of a passive solar greenhouse.

The purpose the project is to assist the farm increase the production of healthy crops to ensure food security, sovereignty and establish water rights into the next century.

(1)FUTURE INDIAN WATER SETTLEMENTS IN ARIZONA: THE RACE TO THE BOTTOM OF THE WATERHOLE? John B. Weldon, Jr. & Lisa M. McKnight

(2)FEDERAL RESERVED WATER RIGHTS, BLM

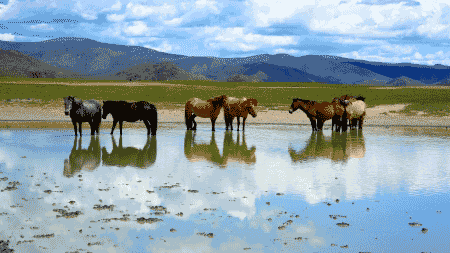

LET'S LEARN FROM THE HERD

HSP Organizes New Partnership for Equine Assisted Therapy

The mission of the Highland Support Project is to foster the growth of social capital that enables people to work together to access opportunities and create a better world. One aspect of this endeavor is promoting the values and norms that permit cooperation and seeking the common good.

Adam Smith, the famed Scottish philosopher and author of the Wealth of Nations, also penned the Theory of Moral Sentiments in which he argues that empathy is the critical natural trait that enables humans to achieve civilization and this mirrors a Maya teaching about the importance of harmony for a healthy society.

“There are striking similarities between horses and people,” says Dede Beasley, M.Ed., LPC, an equine therapist at The Ranch, who grew up riding horses and has maintained a private practice counseling individuals, couples, and families for 30 years. “Like people, horses are social beings whose herd dynamics are remarkably similar to the family system.” (1)

It is not a surprise to those who have had a dog or a horse as a friend to learn that herd animals have developed high levels of emotional intelligence that extend beyond the borders of species. Clinical research confirms that animal therapy benefits include:

- Improved fine motor skills,

- Improved balance

- Increased focus and attention

- Increased self-esteem and ability to care for oneself

- Reduced anxiety, grief, and isolation

- Reduced blood pressure, depression, and risk of heart attack or stroke

- Improved willingness to be involved in a therapeutic program or group activity

- Increased trust, empathy, and teamwork

- Greater self-control

- Enhanced problem-solving skills

- Reduced need for medication

- Improved social skills

Because many children, teens, and adults enjoy working with animals, animal-assisted therapy can be particularly beneficial for individuals who are resistant to treatment or have difficulty accessing their emotions or expressing themselves in talk therapy.(2)

The Highland Support Project has initiated a partnership with the Fort Apache Historical Foundation and the Apache Behavioral Services to develop an Equine Therapy program housed in the historic stables that once housed the rides of the famed Buffaloe Solders.

The objective of the program is to offer culturally relevant, holistic therapy alternatives to a population that presents common indicators of historical trauma.

While we are in the beginning stages of rehabbing the stables and constructing riding corrals, we envision this program to include trail rides and other commercial equine activities that will provide employment and enterprise development opportunities through culturally supportive tourism.

We also identify this as part of the solution to the challenging issue of wild horses and the economic and ecological impact these herds have on tribal lands throughout the Southwest.(3) No ones like to have the well-being of horses in competition with the needs of tribal members. The unfortunate problem arises from the exponential growth of herds where there are no natural predators. We hope to provide a business model capable of maintaining the sacred relationship of Apache people and the Mustang herds.

HSP is organizing work teams starting Spring 2017 to work on the corrals and rehabbing of the stables. We will also have trail development and maintenance opportunities perfect for youth groups. For more information, register here.

(1) 5 Lessons People Can Learn From Horses in Equine Therapy

HSP's 2015 Annual Report

How Food Culture in Guatemala Reflects the Principles of Maya Cosmovision

Dedicated to the women of AMA.

This article explores my reflections on food culture in Guatemala following an action research inquiry into food sharing and storytelling working with the Asociación de Mujeres del Altiplano (AMA) between May and August 2016. I argue that Mayan food culture reflects the wider principles of Mayan cosmovision and propose that these principles could provide a guide to leading a more ethical, fulfilled and balanced life.

Contrasting food cultures

There is the purchase and consumption of food to meet our physical needs and then there is the culture that incorporates the cultivation, harvest, production, preparation and act of eating food. Esteva and Prakash (2014) who discuss this distinction in their book, ‘Grassroots Post-modernism Remaking the Soil of Cultures’ compare ‘alimento’ defined as the industrial process of buying and consuming food common in many globalised western cultures with ‘comida culture’, which encapsulates the holistic culture around food found in many indigenous cultures like the Maya. It was this holistic, indigenous food culture I uncovered as part of my inquiry with AMA.

There is the purchase and consumption of food to meet our physical needs and then there is the culture that incorporates the cultivation, harvest, production, preparation and act of eating food. Esteva and Prakash (2014) who discuss this distinction in their book, ‘Grassroots Post-modernism Remaking the Soil of Cultures’ compare ‘alimento’ defined as the industrial process of buying and consuming food common in many globalised western cultures with ‘comida culture’, which encapsulates the holistic culture around food found in many indigenous cultures like the Maya. It was this holistic, indigenous food culture I uncovered as part of my inquiry with AMA.

What’s mine is yours

‘No me vas a depreciar Simone’ (you’re not going to refuse me are you Simone?) was the response on the rare occasion I turned down someone’s offer to share the food they had brought. Trying to uphold my British politeness I had tried to refrain from taking from those that I assumed had the least to offer. However, I came to learn that refusing food offered in Guatemala was actually one of the worst kinds of cultural offense. No matter how small the offering it would be divided up and passed around by colleagues for ‘la refa’ (break time) whether it’s a glass of blended fruit, a sugared toasted bread or simply a slice of orange.

Another example of the food sharing culture took place at lunchtime in the AMA office. Women working in the textile workshop would habitually file out one by one into the kitchen at the same time every day to eat together. Huddling around the microwave as if it were an open fire they would reheat the food prepared that morning or the leftovers from the night before, always accompanied by freshly made tortillas. If there had been a family celebration homemade corn tamalitos or chuchitos (corn balls stuffed with meat stew) would be proudly distributed like wedding favours, individually wrapped in dried corn leaves and steamed over a wood-burning stove. If it were midweek or approaching payday more humble vegetarian dishes would appear, sopa de arroz (rice soup), torta de huevo (egg flan) or veduras envueltas (vegetables fried in egg). Before sitting down to eat everyone would systemically hand out morsels of their serving to the others present and make space on their plate in anticipation to receive the reciprocal gifts; ‘aunque solo tortillas y queso’, ‘even if it’s only tortillas and cheese’ as Guadalupe Ramirez, the Founding Director of AMA would say. I saw the same custom in the rural communities I visited over the years, where I was always offered a drink or snack upon entering a home.

Another example of the food sharing culture took place at lunchtime in the AMA office. Women working in the textile workshop would habitually file out one by one into the kitchen at the same time every day to eat together. Huddling around the microwave as if it were an open fire they would reheat the food prepared that morning or the leftovers from the night before, always accompanied by freshly made tortillas. If there had been a family celebration homemade corn tamalitos or chuchitos (corn balls stuffed with meat stew) would be proudly distributed like wedding favours, individually wrapped in dried corn leaves and steamed over a wood-burning stove. If it were midweek or approaching payday more humble vegetarian dishes would appear, sopa de arroz (rice soup), torta de huevo (egg flan) or veduras envueltas (vegetables fried in egg). Before sitting down to eat everyone would systemically hand out morsels of their serving to the others present and make space on their plate in anticipation to receive the reciprocal gifts; ‘aunque solo tortillas y queso’, ‘even if it’s only tortillas and cheese’ as Guadalupe Ramirez, the Founding Director of AMA would say. I saw the same custom in the rural communities I visited over the years, where I was always offered a drink or snack upon entering a home.

This culture of food sharing is symbolic of the Mayan philosophy ‘Yo Soy Tú y Tú Eres Yo’, ‘I am you and you are me’, where there the individual self does not exist, only the collective (Matul, 2007). This principle says that I am okay when you are okay, if I eat, you will eat. It illustrates the inherent interest in collective wellbeing over individual wellbeing. Indeed, it demonstrates empathy at the most profound: we are each other. Contrast this with the English phrase, ‘what’s mine is yours and what’s yours is mine’. Although at first the distinction may appear nuanced, unpack this a little further and the phrase, although generous in its intention, reflects the (capitalist) notion of ownership. This juxtaposes the Mayan worldview that everything on this earth is in fact on loan. We do not own land or the earth’s resources but must care for them respectably, only taking what is essential. Things are no more mine than they are yours. This comparison left me pondering how different our world might look today if we had adopted indigenous food practices rather than the encroachment of western fast food culture around the globe.

Closely linked to this sharing culture is the notion that eating is a communal ritual in Guatemala. ‘Donde comen dos comen tres’ was the phrase I learned at the beginning of my four years living in Guatemala. If there’s enough for two there’s enough for three, meaning there’s always sufficient food to go around, be it with family, friends, neighbours or even strangers. This was something Guadalupe recounted during our interview (July, 2016). She recalled her father’s occasional dismay when returning home at the end of a working day to find a horde of children squeezed around table at dinnertime, ‘how many children do I have today?!’ he would exclaim. Indeed, I learned far too late that if someone asks you to stay for dinner you must never refuse the invitation. In Guatemala, the pleasure of food comes from the act of sharing so there is always room for one more.

Closely linked to this sharing culture is the notion that eating is a communal ritual in Guatemala. ‘Donde comen dos comen tres’ was the phrase I learned at the beginning of my four years living in Guatemala. If there’s enough for two there’s enough for three, meaning there’s always sufficient food to go around, be it with family, friends, neighbours or even strangers. This was something Guadalupe recounted during our interview (July, 2016). She recalled her father’s occasional dismay when returning home at the end of a working day to find a horde of children squeezed around table at dinnertime, ‘how many children do I have today?!’ he would exclaim. Indeed, I learned far too late that if someone asks you to stay for dinner you must never refuse the invitation. In Guatemala, the pleasure of food comes from the act of sharing so there is always room for one more.

Space and time: add two essential ingredients and stir

Space and time are both essential ingredients of a healthy ‘comida’ culture. In western fast food culture we have become accustomed to eat lunch as quickly as possible. During workdays we are constantly rushing, often eating standing up or while travelling to save time; at best sat down but in front of an electronic device multitasking. Food thus becomes merely a consumptive process rather than a ritual to nourish the body, mind and spirit. In Mayan food culture the act of eating is inseparable from the ritual of making time to sit down to eat together in the kitchen: the heart of the home as Guadalupe describes.

Space to reflect

Food carves out a reflective space within the daily grind. In Guatemala this space is centred on one of three things: the fire, the stove or the table. In most rural areas it will predominantly be the fire. Indeed, most women’s days are planned around food, beginning at the crack of dawn to light the fire to make the Nixtamal or coffee and being attentive throughout the day to add more firewood, often fetched by hand from the surrounding mountainsides. Olivet Lopez (2015) in her article ‘Life Around the Firewood Stove: The Impact of Price Volatility,’ discusses how stoves or fires in the Highland areas of Guatemala not only provide the family’s sustenance but also keep family members warm on the cold Highland evenings. Thus the fire acts as a unifier, bringing the family together. Family members huddle around in a circle to share events from the day, news from the community or stories from days gone by. It is the place where family decisions are made, and household customs such as cooking or weaving are passed down from mother to daughter. Learning in this space is based around the oral tradition of storytelling to transmit knowledge from one generation to another through the maternal tongue where mysticism and history intertwine to ground children in ancestral wisdom while guiding them towards the uncertain future.

Food carves out a reflective space within the daily grind. In Guatemala this space is centred on one of three things: the fire, the stove or the table. In most rural areas it will predominantly be the fire. Indeed, most women’s days are planned around food, beginning at the crack of dawn to light the fire to make the Nixtamal or coffee and being attentive throughout the day to add more firewood, often fetched by hand from the surrounding mountainsides. Olivet Lopez (2015) in her article ‘Life Around the Firewood Stove: The Impact of Price Volatility,’ discusses how stoves or fires in the Highland areas of Guatemala not only provide the family’s sustenance but also keep family members warm on the cold Highland evenings. Thus the fire acts as a unifier, bringing the family together. Family members huddle around in a circle to share events from the day, news from the community or stories from days gone by. It is the place where family decisions are made, and household customs such as cooking or weaving are passed down from mother to daughter. Learning in this space is based around the oral tradition of storytelling to transmit knowledge from one generation to another through the maternal tongue where mysticism and history intertwine to ground children in ancestral wisdom while guiding them towards the uncertain future.

Time to Prepare

Many of the typical dishes here in the Guatemalan Highlands require hours of careful preparation. Yet cooking is considered, by most, a labour of love rather than a fastidious chore. This was confirmed by several of the AMA’s team members who expressed to me their joy in having time to cook at the weekend in the comfort of their own kitchens when the process of cooking transformed into a leisure activity. Much to my dismay, cooking processes cannot be rushed nor short cuts taken. Take the preparation of tortillas in an indigenous Highland community for example. To make tortillas using the traditional method one must first ask God’s permission to harvest the corn; this may involve prayer, candles, incense and song. Corn kernels are skilfully plucked off the husks one by one then laid out ceremoniously to bask in the sun like adorned yellow tapestries until dry. The dried corn must then be soaked in an alkaline solution (to unlocked essential nutrients) before being ground into a pulp. This is then mixed with water to form ‘la masa’ (tortilla dough) ready to mould into tortilla-shaped circles that are toasted directly on ‘la plancha’ (stovetop). This elaborate process provides spiritual, emotional as well as nutritional sustenance. As my palate grew attuned to the subtle differences in tortilla types, I realised the taste of homemade tortillas is incomparable to the packet flour variety.

Many of the typical dishes here in the Guatemalan Highlands require hours of careful preparation. Yet cooking is considered, by most, a labour of love rather than a fastidious chore. This was confirmed by several of the AMA’s team members who expressed to me their joy in having time to cook at the weekend in the comfort of their own kitchens when the process of cooking transformed into a leisure activity. Much to my dismay, cooking processes cannot be rushed nor short cuts taken. Take the preparation of tortillas in an indigenous Highland community for example. To make tortillas using the traditional method one must first ask God’s permission to harvest the corn; this may involve prayer, candles, incense and song. Corn kernels are skilfully plucked off the husks one by one then laid out ceremoniously to bask in the sun like adorned yellow tapestries until dry. The dried corn must then be soaked in an alkaline solution (to unlocked essential nutrients) before being ground into a pulp. This is then mixed with water to form ‘la masa’ (tortilla dough) ready to mould into tortilla-shaped circles that are toasted directly on ‘la plancha’ (stovetop). This elaborate process provides spiritual, emotional as well as nutritional sustenance. As my palate grew attuned to the subtle differences in tortilla types, I realised the taste of homemade tortillas is incomparable to the packet flour variety.

Taking time to chew the fat

Time is not only required in the preparation but also the consumption of dishes. Observing table habits at lunchtimes I soon realised that the foreigners among us would sometimes finish up to 30 minutes earlier than the rural indigenous diners. I could not fathom how people took so much time to finish their food until I reflected that this is really how it should be: dedicating time to relish every mouthful of a meal that someone has lovingly prepared.

Hence, mealtimes are sacred spaces. Lunchtimes at AMA parted the never-ending busyness of the workday into two, relieving the stress that had crept up over the morning’s hours. Lunchtimes were never forfeited, no matter how late in the day it arrives. Hence for the staff that eat in the office lunchtime was nonnegotiable; it was a time that could never be rushed. Observing through a western lens many have assumed this was a sign of laziness but this would be a misjudged assumption. Lunch is probably the most important meal of the day in Guatemala where some of the most effective learning and communication take place whether at home or at work over lunch. At AMA it was a space where colleagues caught up on one another’s working days, their experiences out in the community or particular exchanges. They told stories, shared recipes or reflected on philosophical life questions, probing into others’ thoughts and feelings about the particular theme of the day or inquiring about the current status of their family’s harvest. I probably learned more at the table than anywhere else in my inquiry.

Conclusion: a takeaway of a different kind

It was a love of food that led me to focus my research around the culture of food sharing and how this could facilitate organisational change processes. Yet through the medium of food I unexpectedly discovered a more profound ontological lesson: a blueprint for living a more fulfilled, peaceful, and balanced way of life. A blueprint founded on the principles of reciprocity that emphasizes giving rather than taking and puts others’ needs before our own. In a food culture where there is always room to feed one more, and enough time to sit, be still and chew the fat. Here, the space to eat, carved out by a fire, a stove or a table becomes sacred: a time to connect – physically, emotionally and spiritually with those with whom we share the space thanks to the food that brought us together.

By Simone Riddle

AMA is an indigenous women’s association working to empower communities in the Highlands of Guatemala. Simone worked with AMA between 2011-2013 and returned to undertake an action research inquiry with AMA as part of a Masters programme at the Institute of Development Studies in the UK. She is a Board member for AMA’s sister organisation, the Highland Support Project based out of Virginia and has a Latin American food blog, lasalsainglesa.com.

References

Esteva, G., Prakash, M. S., & Shiva, V. (2014). Grassroots Post-modernism Remaking the Soil of Cultures. Zed Books.

Matul, D. (2007) La Cosmovisíon Maya. 2nd edition. Vol. 1. Ciudad de Guatemala: Liga Maya de Guatemala.

Olivet Lopez, A. L. (2015). Life Around the Firewood Stove: The Impact of Price Volatility.

IDS Ramirez, G. (2016) interview, AMA, Quetzaltenango, Guatemala.

Getting to Know Dilworth UMC

[huge_it_gallery id="9"]

5 hardworking and fun-loving ladies from Dilworth United Methodist Church in Charlotte, North Carolina came to experience rural indigenous life in Guatemala for their 1st mission trip with HSP. The team built 5 stoves in the community of Caserío Belen, San Juan Ostuncalco, and carried out their Maya Arts Project (MAP) in a rural school in the neighboring community of Chanshenel.

During the construction of their stoves, many family members were actively involved with our Dilworth partners and enjoyed helping them mixing cement and carry blocks. One of AMA's women's circle members and current stove beneficiaries was in the middle of having her new house built. She dictated where the future kitchen would be and the stove was built in the open air through rain, cold and wind; but our Dilworth partners were happy as ever to help bring her homeowner's dream alive with the addition of an improved stove.

With only 5 members of the team, the Dilworth ladies bravely led 2 MAP projects to over 100 students, from grades 1-6. It was a busy morning, to say the least. The director of the school commented that the government only gives them about 200 Quetzales per year (approximately $26.00) to buy all of their supplies for the total of 130 students, including those in pre-primary. Because of this, they cannot afford art supplies like paint, glitter, brushes, canvas, etc., that HSP supplies MAP with. The students rarely get to let their creativity shine through elementary art and so they were ecstatic to paint, glue, cut, and play on that special day. The joy and excitement on their faces to learn about their Maya culture through art and creativity was something that warmed all of our hearts and kept us smiling for the rest of the day.

We look forward to continuing our partnership with the loving hearts of Dilworth UMC for another mission trip in the future. Until next time, thanks to our lovely team for choosing to do their summer mission trip through the transformational development model of HSP!

Experiencing the Symmetry of HSP with Shiloh UMC

According to Mayan cosmovision, we are not seen as separate from our environment but rather we are known to have been created from it. All matter on earth is made up of the same particles as stars, and Maya mythology tells that we first formed into humans as corn growing from the earth.

Just as how we as Highland Partners come to Guatemala to understand and experience another culture, we leave part of ourselves behind. The process is reciprocal, Highland Partners come to initiate sustainable change in rural communities and subsequently are changed internally. The community of Manantial will always see Shiloh’s warmth in the flames of their stoves, and their spirit in the trees planted on their land.

According to Mayan cosmovision, we are not seen as separate from our environment but rather we are known to have been created from it. All matter on earth is made up of the same particles as stars, and Maya mythology tells that we first formed into humans as corn growing from the earth.

Just as how we as Highland Partners come to Guatemala to understand and experience another culture, we leave part of ourselves behind. The process is reciprocal, Highland Partners come to initiate sustainable change in rural communities and subsequently are changed internally. The community of Manantial will always see Shiloh’s warmth in the flames of their stoves, and their spirit in the trees planted on their land.

Thank you, Shiloh UMC for your participation in HSP’s methodology of transformational development that empowers marginalized native communities. You have planted the initial seed of this process for 5 families with a clean-air cook stove and 50 new trees.